Funding, funding, funding. It’s all many founders, and most of the popular media, seem to care about. Yet, getting funding is not a guarantee of success. Far from it. In fact, there are a number of hidden costs associated with getting funding that founders ignore at their own peril.

1. Trying to get funded is a full-time job (or, the opportunity cost of courting)

When you start a business, you know it’ll be a full-time job (and almost certainly more). And that doesn’t even include trying to get funding. Unless you already have product/market fit with an established customer base that provides growing monthly recurring revenue (and, if you do, chances are VCs are approaching you), getting funding is hard and time consuming. You may have a great idea, but so do most other founders who approach VCs. Given the shear quantity of companies courting VCs, it’s not hard to see why you will get rejected, time and again, by most of the VCs you approach. This is a major time suck and an emotional drain.

Even worse, there is a significant opportunity cost associated with trying to get funding. Think of all the other things you could (and in most cases, should) be focusing on: building the right product, talking with potential customers, hiring the right people, setting up marketing campaigns, establishing the right culture, and much, much, more. So while getting a few million dollars in VC funding might help your company grow, the question you should be asking yourself is actually much more complicated: “Does the high cost of looking for funding outweigh the potential benefits of actually getting funded?” In many cases, the answer is ‘yes’.

2. Funding can actually reduce your runway

This is a seemingly counter intuitive point. Runway is defined as “the amount of time until your start-up goes out of business, assuming your current income and expenses stay constant.” So it would seem that getting funded would increase your runway. Not necessarily.

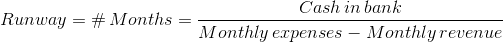

To understand why, we have to delve into a bit of elementary math. A simplified way to calculate runway is:

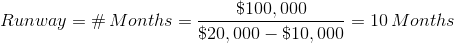

Supposing your company had $100k in the bank, your monthly expenses were $20k, and your monthly revenue was $10k, your runway would be:

In plain English, that means that all else being equal, your start-up has 10 months left before it runs out of money. Now, let’s imagine you received VC funding worth $1 million. Here’s your new runway:

Great news, the $1 million in VC funding gave you an extra 100 months of runway! Not so fast. To arrive at an extra 100 months of runway, we’ve made one critical assumption: that after receing funding, your expenses will stay the same. For most start-ups this is not the case. Think about it. You didn’t raise a bunch of cash to let it sit in the bank. No, you raised the cash in order to hire more people, lease additional office space, put new marketing plans into action, provide additional perks to employees, and more. Thanks to getting funding, it’s easy to imagine your expenses increasing from $20k per month to perhaps $150k per month. Let’s look at your new runway:

The extra $1 million in funding has actually decreased your runway by over two months! Yes, I’ve assumed that your monthly revenue doesn’t increase as a result of the injection of cash, but the point remains the same. VC funding can, and in many cases does, decrease your runway.

3. Loss of control

This one is perhaps more obvious. Founders quit their jobs to start their company for many reasons, but one of the most common is that they want to regain control over their lives by becoming their own boss. For bootstrapped companies, this dream can easily become a reality. Not so for venture-backed start-ups. Most VCs will want a seat on the Board of Directors, many will involve themselves in the company’s strategic decisions, and some may even make their funding contingent on replacing you as CEO. Depending on your goals as a founder, this may or may not be acceptable, but getting a VC involved with your start-up certainly involves giving up a lot of control over the business you worked so hard to found.

4. Loss of potential upside

The potential for a large financial payoff may not be your primary motivation for starting a company (in fact, it shouldn’t be). Nevertheless, have you ever met a founder who didn’t dream of financial success? Me either. With this in mind, think twice before accepting VC funding. To explain why, let me paint a picture of two successful companies:

Company A

This company is bootstrapped and the sole founder controls 100% of the shares. It recently sold for $10 million (yay!), and the founder keeps all $10 million.

Company B

This company took multiple rounds of VC-funding, and as a result of dilution, the sole founder controls only 10% of the equity. In order for the founder to make the same $10 million as the founder of Company A, his company will have to sell for at least $100 million (10% of $100 million).

Building a $10 million company is hard enough. Build a $100 million company is a completely different story. For most founders, the trade-off is simply not worth it.

5. The goals of those who fund are often not the goals of those who found

VCs and founders don’t always see eye-to-eye, to say the least. The VC business model relies on positioning companies for a quick and highly lucrative exit (irrespective of whether that exit is via acquisition or IPO). Without an exit, VCs will never make enough money to justify their initial investment. In fact, the type of company that VCs hate the most is the “living dead” (companies that are not hitting it out of the park, but aren’t running out of cash either. These zombie companies simply live forever, making reasonable, but not incredible, amounts of money. VCs hate them because they are a time-suck. They are still part of the VC’s portfolio, yet their potential upside is limited).

“Living dead” companies may be a VC’s worst nightmare, but for many of their founders, they aren’t so bad. They might not lead to a $100 million IPO, but they can still easily lead to becoming part of the 1%. In short, founders of most “living dead” companies are able to live a very comfortable lifestyle.

But since VCs want a big exit, they will push you to make decisions that lead to a big exit. While on the surface this sounds great, there are consequences. As a founder, you may wish to grow slowly as you find product/market fit. VCs probably won’t like this. As a founder, you may have an offer to be acquired, but might not be ready to give up control and want to decline. VCs may not like that, either. In short, the goal of every VC is to make a lot of money, as quickly as possible. That’s not the goal of every founder, every time.

In Summary

All this goes without saying that for some start-ups, getting funding can be the right choice. The word “strategic” is overused in the business world, but in this case it applies. Start-ups should look for funding for strategic purposes only (for example, when the success of the business depends on being able to expand quickly, or when the business is capital intensive). In all other cases, founders should think twice before approaching VCs. The hidden costs in getting funding can be quite high.

![Money-Increase-512[1]](http://www.dshorowitz.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Money-Increase-5121.png)